Corey Dieterman | Houston Press

In 1979, disco was all the rage. For all the kids who had never bothered to pay attention when their parents would talk about it, it was sort of like dubstep. It was ubiquitous on the radio and even rock bands were vying to get in on the action so they didn’t get left behind in the new revolution. Sort of like how Korn did that album with Skrillex, only a little bit less horrible.

Even punk bands were reluctantly dragged into it. In 1978, Johnny Rotten launched his post-punk band Public Image Ltd., which, for all its punk cred, did employ a number of disco beats. Around the same time, two of the biggest rock bands in the world were planning new records and silently plotting to work on their own disco singles.

Even punk bands were reluctantly dragged into it. In 1978, Johnny Rotten launched his post-punk band Public Image Ltd., which, for all its punk cred, did employ a number of disco beats. Around the same time, two of the biggest rock bands in the world were planning new records and silently plotting to work on their own disco singles.

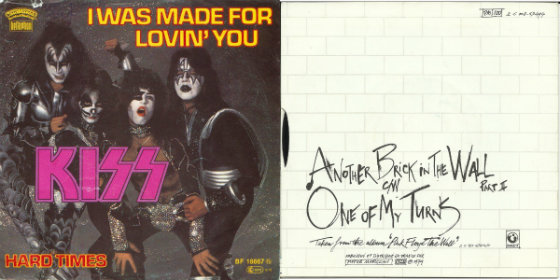

Those bands? Pink Floyd and KISS. And oh boy, what those plans wound up wreaking.

In early 1979, Pink Floyd was hard at work sifting through the mess of demos Roger Waters had recorded during their break after the Animals tour concluded. The mostly acoustic demos were high in number and low in quality. If you’ve ever heard them (they’ve been bootlegged for years), it’s a wonder Floyd was able to parse an album out of them at all.

A whole album ended up on the cutting-room floor and became Waters’ first solo record,The Pros and Cons of Hitchhiking. Some other cuts ended up on The Final Cut and one or two made into the film version of their upcoming album, but were ultimately left off of what would become The Wall.

However, one track in particular got some special attention from Waters, lead guitarist David Gilmour, and producer Bob Ezrin. It was a three-song suite called “Another Brick in the Wall,” at the time simply a rough acoustic-guitar demo with Waters whispering over it. But more on that later.

While Floyd was in France working on that, an entirely different band was in New York, working on their own demos for an upcoming record. KISS was making what would eventually become the Dynasty album, hot off the heels of the second volume of their Aliveconcert-recording series and simultaneously=released solo records by all four members.

By this time, Peter Criss was being replaced regularly by session drummers and the remaining KISS members were looking outside themselves for songwriting ideas. They had come about as far as they could on the pure “rock” sound, and both Gene Simmons, ever the consummate businessman, and Paul Stanley were looking into what they could do to keep up with current trends.

Enter Stanley with a legendary idea. “Let’s write a disco song. How hard could it be?” he said. (Okay, I don’t know if he really said that, but it’s as close to the truth as necessary.)

In any case, apparently Stanley believed the disco sound, which was dominating the airwaves, to be exceptionally easy to write, so why not try it? Meanwhile, the band had just hired professional songwriter Desmond Child (who would eventually co-write most of Aerosmith’s ’90s hits) and producer Vini Poncia, who spruced up his demo for what would become “I Was Made for Lovin’ You.”

Released in May 1979, it was an instant hit on the radio. Even Simmons wasn’t a fan of the track, it immediately went platinum and he liked that. KISS fans thought the band was “selling out,” but KISS probably couldn’t hear them over all the money they were making. Child later commented that they had created “the first rock-disco song” and while that may not have been true, it certainly made a bigger splash than any other.

However, it was the first sign of attrition in KISS’s literal dynasty. The recording marked the very moment when KISS began to lose credibility, something they would only compound upon themselves into the ’80s by releasing album after album of gimmick after gimmick (including a failed concept album produced by none other than Bob Ezrin), trying to capture the public’s imagination once more.

Meanwhile, back in France, Pink Floyd put the finishing touches on their Wall album and released it in late 1979. During the time they had been recording it, the band had dealt with high amounts of tension and infighting, especially with the increasingly distant and egotistical Waters dominating the sessions with his new favorite collaborator, Bob Ezrin.

One of the most tenuous parts of the session was when Ezrin suggested that Floyd get in on the disco wave. Lord knows where he heard it when he listened to Waters’ demo of “Another Brick In the Wall,” then titled “Education,” but he decided the track needed a disco beat and that it should be the first single.

Waters was on board, but Gilmour was displeased. Ezrin had told him to visit a disco club, popular in those days, to see what he thought of it and, in his own words, it was “god awful.” Eventually, Gilmour was overruled on “Another Brick In the Wall,” along with just about everything else to do with the album, and the disco beat was put in the song.

Released immediately after the record came out in November 1979, “Another Brick In the Wall” was an instant hit. It topped the Billboard charts in the UK and America and propelled The Wall to No. 1 in seven countries. It has become one of the band’s signature songs and most enduring hits. You can hardly turn on a classic-rock station in America without hearing it at some point in the hour.

Best of all, though, it alienated no fans. Not one single Pink Floyd fan has ever heard the song and said, “Hey, that’s a disco beat. Fuck Pink Floyd, those sellouts!” So why did it work for Floyd and ultimately doom KISS in the long run?

Because it still sounded like Pink Floyd. “Another Brick in the Wall,” despite its disco beat, retained Floyd’s character. The lyrics were dark and in line with everything Waters had previously written. The guitar still drew on Gilmour’s blues influence. It conveyed a powerful message and it was bleak, just like Floyd had been for ages. It was just as much Floyd as “Welcome to the Machine” or “Time.”

|

But “I Was Made for Lovin’ You,” solid track or not, wasn’t KISS. It was someone, but it wasn’t the KISS fans had grown to love.

It wasn’t the demonic hard-rock band of Destroyer, it wasn’t the crowd crushing band who played Alive (mostly in the studio), and it certainly was no “War Machine.” It wasn’t the sort of thing that was going to piss off parents. It was glitzed-up schmaltz, lyrically and musically. Even Simmons commented that it sounded like the Four Seasons.

The lesson here, kids, is that it’s always good to experiment and incorporate new sounds, but you have to stay true to yourself. If you recklessly abandon everything that ever made your sound to begin with just to chase a fleeting trend, you’re going to get left in the dust when that trend dies.

You’ll end up just one more regrettable remnant of a sound long dead and long regarded an embarrassing oversight in the history of rock.