Classic Rock

Iggy Pop claimed that he killed the 60s, but it turned out it was four semi-normal guys right off the streets of New York who really drove the final stake through heart of the peace-and-love decade nearly 46 years ago.

Gene Simmons, a former elementary school teacher; Paul Stanley, a cab driver with a heart-shaped face; Peter Criss, a sometime butcher and itinerant drummer who studied under the mighty Gene Krupa; and Ace Frehley, a gang member-cum-liquor delivery man. They stormed out of a $40-a-month fourth-floor walk-up in New York’s Chinatown in their six-inch platforms and sweaty black leather looking like four beasts disgorged from the underworld, and unleashed an unholy and entirely masculine creed of sex, braggadocio, innuendo and conquest, all delivered at a screeching 110 decibels and addressing every young man’s fantasies.

While the band’s message has changed over the years (they’ve become more family-friendly and forswear any cursing during the show), they still attract legions of foot soldiers into the Kiss Army – even now, when they’re calling it quits in one final tour they’ve dubbed the End Of The Road. (They’ve attempted to trademark the term with the US Patent office to prevent any other retiring bands from using it. Good luck with that.) So far, 44 shows have been played in North America, with another 25-date run beginning in August. The European leg begins next week, and there are plans to extend the tour until, probably, mid-2020.

While the band’s message has changed over the years (they’ve become more family-friendly and forswear any cursing during the show), they still attract legions of foot soldiers into the Kiss Army – even now, when they’re calling it quits in one final tour they’ve dubbed the End Of The Road. (They’ve attempted to trademark the term with the US Patent office to prevent any other retiring bands from using it. Good luck with that.) So far, 44 shows have been played in North America, with another 25-date run beginning in August. The European leg begins next week, and there are plans to extend the tour until, probably, mid-2020.

Back at the beginning, the band were fuelled by high ambition, an unrelenting will, a prodigious work ethic and only the most rudimentary of musical talents. But they not only changed the face of musical history by painting it in Stein’s Clown White, they also kicked off their own brand of revolution, putting music back in the hands of the ordinary people and turning it back into a populist manifesto, picking up where Grand Funk Railroad left off by knocking rock music off of its lofty perch, stripping it of its perfect hair, wrecked cool and tight velvet stovepipe pants.

Prior to Kiss, rock stars seemed to exist in some distant Valhalla, breathing saffron-scented air, buying and wrecking Aston Martins, imbibing rare substances worth a king’s ransom and rarely consorting with mere mortals unless they looked like supermodels or Beatle wives. In short, rock stars were not like the rest of us.

But the members of Kiss were. They were a little unfinished. Outsiders, really, not the captains of the football team with a blonde cheerleader on their arm. Instead they more resembled the guy who sat next to you in Advanced Mathematics class. Meaning they were smart guys. Smart enough to know their history, and figuring out it was just about time for a sea change.

“It was the mid-seventies, and people had had enough of the hippie, political thing and just wanted to have a good time,” Gene Simmons explained a few years ago. In the early days, Paul Stanley was fond of saying: “We are our fans.” While not exactly true, it was an appealing notion. These days he’s altered it a little, saying: “Our fans may not look like us but they can feel like us. I think that in our own way we’ve motivated people to, in their own way, be Kiss. Whether it’s to become a writer, whether it’s to become a country singer, whether it’s to become an attorney, you name it.”

Maybe at the heart of it was that Kiss has always been more than just a band. It was a state of mind; a place where feeling alienated was venerated, where boys were men, girls were groupies and nobody ever had to turn down the volume. But there’s something compelling about the egalitarian ideal that anyone could do what Kiss did. Kiss weren’t obviously handsome, rich, cultured, preternaturally talented, advantaged or even art-school dropouts like their British counterparts, but the implied message was that, given the right circumstances and drive, anyone could become a rock star.

But to be accurate, self-empowerment wasn’t really their early mission. That was to be bigger than the New York Dolls!

“Yes, that’s true,” says Simmons. “I remember Paul and I went to see the Dolls play at a local thing in New York City. It was right at the beginning; they came about six months before us. Paul and I were in the back of the hall, and we had our big hair, trying to look cool, but nobody knew us.

“The Dolls came on stage and we said: ‘Wow, they look like real rock stars.’ Then they started playing, and we looked at each other and, so help me God, I might’ve said it to him or he might’ve said it to me: ‘We’ll kill ’em.’ You could see the lust and the blood running from our mouths as we vowed: ‘We’ll fucking destroy them.’

“They had the swagger and everything else, but they just couldn’t play or sing; no harmony, the guitar playing was deficient. But boy they looked good. So Kiss was designed consciously as: let’s put together the band we never saw on stage.”

By doing that, they created a band that no one else had seen on stage either. If you don’t count mid-career Alice Cooper.

“They’re a good band. All these guys need is a gimmick,” Cooper commented dryly about Kiss in 1974.

Kiss apparently took that comment to heart, and added more pyro, flash pots, fire-breathing and gushing blood. Frehley had a guitar that shot flames, and Stanley was one of the first artists to hurl himself into the audience – and damn the greasy face-paint slathering over everyone, which became a badge of honour for fans.

Audiences got them, but critics rarely did. Rolling Stone named them the Hype Of The Year in 1975, and legions of reviewers complained that they were “derivative”, “prosaic”, “simplistic” and mostly a joke, a band that catered to the lowest common denominator. It wasn’t until 2014 that Kiss made it to the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame, and then only after fans were allowed to vote.

They were always geniuses at self-promotion. Simmons had quite a bit of practice at self-invention, having emigrated from Israel to New York as Chaim Witz at the age of eight. He became Gene Klein, and began the task of turning himself into an American kid. So fraught with psychic landmines was he that turning himself into the God Of Thunder wasn’t even a stretch.

As for Stanley, he had no less gargantuan a task. “I was a fat, chubby, unpopular kid who disguised himself as a good-looking, cocky frontman in a band, and somehow turned into it,” says Stanley, who at 67 looks 20 years younger. “Hopefully we all find who we are and we become it.”

That self-actualisation, inspirational stuff came later – probably about the time he wrote his book, A Life Exposed, in 2017 – but there was a flicker of it around the time the Kiss Army started swelling in 1979. An incipient fan club, it started as a grass-roots affair in January 1975 by two Kiss fans. They would identify themselves as the President and Field Marshal of the Kiss Army when they called their local radio station to request Kiss records. By the end of 1978, membership in the Kiss Army topped six figures, with merchandise revenues of $100 million a year.

“We definitely tapped into something. And a lot of times we weren’t even aware of it, but we just kind of went with it,” Frehley admitted in 2014. “I always used to say when we were in our peak I felt like I was riding this roller-coaster and I was holding on for dear life. A lot of the things I did were just on instinct, whether it be my songwriting or how I dressed or things I did. Luckily I have good instincts.”

But that wasn’t really true of Stanley and Simmons. They always had a plan for domination – world and otherwise – and stuck to it. Which is exactly why they are winging their way on a private jet to Glendale, Arizona, for the tenth stop on this final tour – and Frehley and Criss are not.

While a Kiss admirer, I wasn’t there at the beginning. And when I did come face to face with these nightmarish figures in wobbly platform heels, abundant chest hair and aggressive face paint, it was by sheer happenstance.

After covering a David Essex record-release bash on the heels of his hit Rock On, I found myself in New York with a free night. Renowned Bowie photographer Leee Black Childers had invited me to a panel he was shooting for NARAS (the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences) and promised dinner afterwards. I said yes, although it wasn’t because I was intrigued that the panel was titled Superstar Or Superstud. It was just the free dinner. I was hoping for the Russian Tea Room.

I was one of the first to arrive at Columbia Records’ Studio B. There were just a handful of people sitting on folded chairs in a small room that couldn’t have held more than 30 people comfortably, but most of the psychic space was already taken up by four looming creatures in fetish wear, looking like warlords from the underworld.

Criss wore a leather vest without anything under it, shivering in the windowless studio. Stanley was stripped to the waist, his chest hair curling menacingly, with a studded dog collar around his neck. Sitting next to him was Simmons, in more elaborate attire: a black leather jacket and pants with strategic holes cut out, and again a bare chest. Frehley was the only one fully covered up, in his futuristic spacesuit, his hair ratted out to there.

At the time, it was impossible to know who was who; they had all switched their nameplates, except for Criss, who didn’t have one at all – a metaphor that would play out over the course of his tenure in the band. But on that chilly October night, Paul Stanley was Ace Frehley, Gene Simmons was Paul Stanley and Ace Frehley, impersonated Simmons with aplomb, aided no doubt by the large gin and tonic in a clear plastic cup before him, something Simmons, a lifetime tee-totaler, would never partake of.

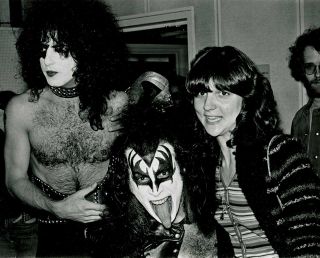

Jaan Uhelszki with Kiss, on the day she met them

Other participants on this forward-looking panel about sex and gender in rock included Danny Fields, a zeitgeist spotter who had discovered Iggy And The Stooges, signed The MC5 to Elektra Records and would go on to manage The Ramones; Wayne/Jayne County, the first transgender rock artist, and part of the Warhol crowd; Jerry Brandt, manager of rock’s second transgender figure, the disturbing Jobriath; industry publicist Connie De Nave; and Richard Robinson, husband of celebrity wag Lisa Robinson and notable at the time for producing Lou Reed’s first solo album.

What struck me that night wasn’t the all-industry star-power gathered in a small room, but that each time the panel mediator, DJ Alison Steele, asked something of the members of Kiss, their reply was: “It’s only rock and roll, but I like it,” no matter what the question. Every single time. They had the sheer bad-boy audacity to not only not do what was expected of them, but also to flaunt it in the faces of what was then the music-industry glitterati. It was chilling how they never broke character once, no matter how awkward and non-sequitur their canned answer was. These were monsters who oozed out a collective nightmare, and they were hell-bent on staying that way for the entire duration of the hourlong panel.

Somewhere around the 20-minute mark, I knew I had to get them into the pages of Creem magazine, where I was a senior editor. I thought they fitted right into our rebellious, there-wasn’t-a-rule-we’d-obey, fuck-you-if-you-can’t-take-a-joke aesthetic.

It appeared I was the only one who thought that way. “They’re New York Dolls clones,” my fellow editor Lester Bangs said dismissively. “Comic-book trash,” spat Dave Marsh. “If you want those clowns in Creem, you’re the one who’ll have to write it,” warned features editor Ben Edmonds. “And it better be fucking good.”

No matter the derision from my colleagues, I knew I was on to something. Recalling that old saw from Victor Hugo written 121 years before Kiss had ever picked up their first tube of lipstick – “There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come” – I was sure that idea had arrived, and that it was wearing black leather.

That’s how I found myself a month later with a craft knife in my hand, sitting in front of a pile of photographs of Kiss in make-up and civilian clothes. In out-takes from the Dressed To Kill album cover, the band members were posed hiding their faces behind newspapers, piling into a phone booth in their suits and ties and then coming out in full regalia, emerging from a subway with fists flourished, performing Herculean tasks in which these four not-so-superheroes saved the world from bland music by sabotaging a John Denver concert. I not unexpectedly titled it ‘Kiss KOMIX’. With that knife, I carved out a dubious niche for myself as the unofficial Kiss Editor.

Over the decades I have continued to monitor that long-standing beat, although I have to say that when I look back I find I miss the era when Kiss were dangerous, inscrutable, inappropriate and just badass.

There was a mystique about the band in those days. Stanley used to say: “I think we get so many groupies because everyone wants to fuck their fantasy or their nightmare. Someone in leather and make-up fucking you must be pretty strange.” It makes one wonder how many times the band members engaged in coitus while suited up.

“It was God Of Thunder, from Destroyer, that turned me on to rock’n’roll, because Gene Simmons sang it,” remembers Babes In Toyland’s Kat Bjelland. “It sounded heavy, mean and evil. Like his soul was being ripped out of his chest. It gave me the shivers.”