With Studio 666 (out Feb. 22), The Foo Fighters continue in a long, not-always-successful tradition of bands attempting movie stardom. The new horror-comedy is a spiritual successor to 1978’s Kiss Meets the Phantom of the Park — one of the most critically maligned yet passionately loved kitsch oddities to emerge from that decade.

The hard rock band’s elaborate costumes, face makeup and pyrotechnic stage shows helped turn them into one of the biggest acts in the world at the time (between 1977 and 1979, they sold $100 million in records and merchandise, roughly $400 million today), and their manager, Bill Aucoin, wanted to take it to the next level. Curiously, Hanna-Barbera, the animation studio behind The Flintstones and The Jetsons, was chosen to produce the TV film for NBC.

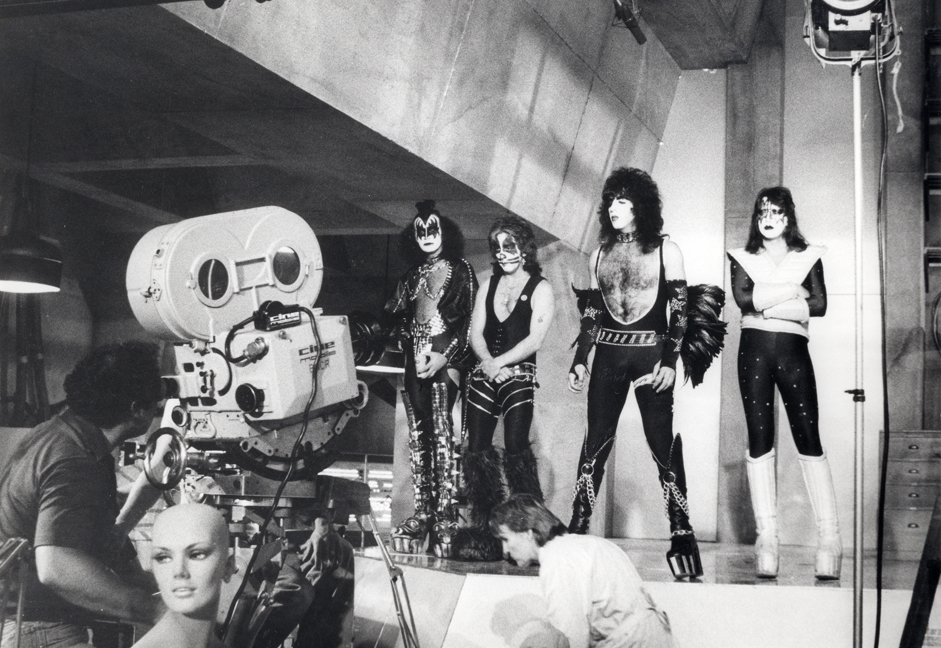

Phantom shot at Magic Mountain near L.A. and followed a mad scientist (Anthony Zerbe) whose animatronic Kiss members do battle with the real ones (who happen to have superpowers like fire-breathing and laser eyes).

“I embrace it like an ugly child,” says Kiss co-founder Paul Stanley. “You have to realize that we were like these imbeciles who got to take over the school. We knew nothing about acting, nothing about filmmaking. We were sold the idea of the film in a sentence that was virtually, ‘A Hard Day’s Night meets Star Wars.’ Well, it was far from either.” If anything, it ended up closer to The Star Wars Holiday Special, which debuted a month later on CBS: an embarrassment that grew into a fan favorite over time.

Stanley, 70, spoke at length with The Hollywood Reporter about the making of the 1978 cult classic.

Seeing Kiss Meets the Phantom of the Park as a child left a huge impression on me. To me, it was the coolest thing ever. And then I was reading up on it, and I saw you guys disowned it. Do you still feel that way?

I guess you would have to define it as kitsch, although it wasn’t supposed to be that in the beginning. But you had four guys who never read the script, who were clueless about even the fundamentals of acting, basically allowed to do whatever we wanted to. And a take was considered anything where we didn’t flub our lines.

How far along were you in this idea of Kiss having a mythology around it when you were first presented with the idea of a movie?

I was trying to place whether the Kiss Marvel Comics came first, but I think Kiss Meets the Phantom may have come first. It is kind of a chicken or the egg, and it was an ugly chicken. [The first Kiss comic book predated the film by one year.]

I don’t remember. I don’t remember much, honestly. When we were introduced to the idea of the film, we basically said, “Make a film? Great.” It was kind of like The Little Rascals. “Let’s put on a show.” There was so much going on at that time. Two members of the band weren’t speaking to the other two members of the band. We had both [lead guitarist] Ace [Frehley] and [drummer] Peter [Criss], who would [act] on whatever whim might cross their mind. They would leave the set in the middle of shooting. In some scenes, we have stand-ins and stunt doubles [playing us]. And the idea of “the talisman” [which gave us our powers] — clearly we’d never heard the term talisman. Look, we were idiots, and we were suddenly put into a position where The Marx Brothers were being taken seriously.

Did it occur to you at the time that you might be making a dud?

I remember that Anthony Zerbe, who was a credible actor, who played the mad scientist — which, every film needs a mad scientist — he was not terribly enamored to be working with us. We weren’t used to being corralled or told what we needed to do. I just remember at one point being on set at Magic Mountain and turning to my manager at the time, Bill Aucoin, and saying: “I think this is going to be horrible.” And he said, “Don’t worry.” You should never hear anybody say, “Don’t worry.” You know?

How did the NBC executives react to the final product?

They gave us a viewing of the film before it aired on NBC. And I just slid further and further down in my chair. By the time it was over, I was looking at chewing gum on the bottom of the seats. I remember a scene where we were levitating some magic box, and you could see the wires onscreen. And in typical Hollywood fashion, when it was over, people were coming over and shaking my hand and congratulating me.

For me, it wasn’t “Springtime for Hitler,” but it’s just interesting how people hold that film in some affectionate memory. And I think that’s terrific. I was there and it wasn’t. I lived it. And whatever you saw on the screen and whatever dubious thoughts you have about it, let me tell you, you just saw the tip of the iceberg that sank the Titanic.

Did you guys make any effort to stop it from airing?

No. We were caught up so much in our fame and this incredible ride we were on, that, no, I didn’t think much of it. But it was also going to be an NBC Movie of the Week. So let other people judge and let other people [say] what they think of it. It was disappointing to me, but I certainly didn’t lose sleep over it. Again, you’re dealing with four guys who had no concept of what making a film was, let alone what was entailed in acting. Literally, before each scene, we would yell out “Line!” and they would feed us the line, and then they’d roll cameras. I said, “Gene, Peter, let’s go, let’s kill the robots.” If I got it all out, that’s a keeper. Let’s move on.

So the Ed Wood School of Filmmaking.

Well, I think that Gordon Hessler, who directed it, and who was a credible director, must have been ready for shock therapy after he worked on that film. It reached a point where after each take, he would ask us if we liked it.

Did it negatively impact your tour sales or your record sales?

Oh, gosh. Nothing could impact our sales at that point. It was viewed by the people who loved us as great, and by the people who didn’t like us as crap.

Did it affect your cool factor at all?

Cool is in the eye of the beholder. There are many people who have always thought we were cool. And there’ve also been many people who thought we weren’t. So we were used to the sticks and stones that were thrown at us. That was part of who we were and who we are. We’ve never played by the rules. Our only rule has always been no rules. We do what we want.

When we started putting out merchandise, it was thought of as completely uncool. Having a fan club was completely uncool. Whereas we thought, if our fans want something, that’s the ultimate cool. If people want to wear a uniform that identifies with us, whether it’s a belt buckle or a T-shirt, they should have it. And although there was a large population of critics and other bands who looked down their noses at it, as soon as those bands saw the kind of income it generated, they all became Kiss clones.

I’m sure I’m not the first person to say this, but to me the genius of Kiss is that you married rock ‘n’ roll to superhero and sci-fi culture.

Yeah. If you gave Superman a guitar and plugged it into a Marshall amplifier, you’d probably have Kiss.

A version of this story first appeared in the Feb. 23 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.